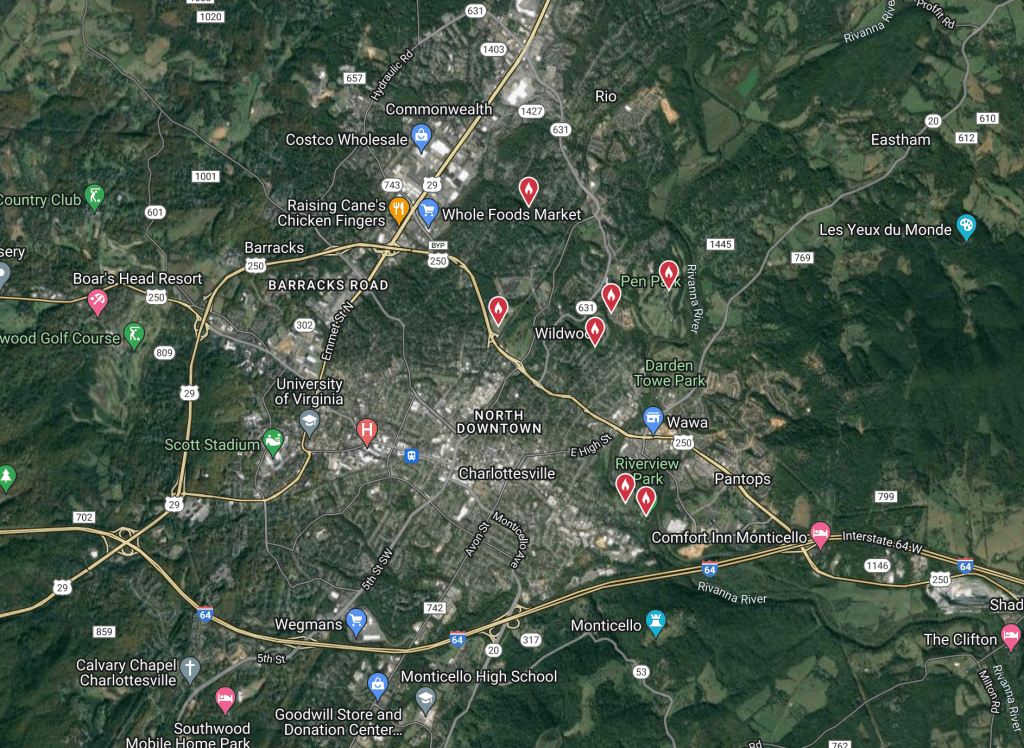

On May 25th my brother Theo and I decided to do a birding “big day” in Charlottesville City. On the surface it was a strange date to attempt to run up a large bird list, as peak spring migration was already two or three weeks in the past. However, I wanted to investigate the status of several uncommon breeding species in the city, (i.e., common merganser, prothonotary warbler) as well as see what late migrants we could find. Theo and I are relatively new residents of urban Charlottesville City, and so in celebration of the fact that we no longer had to drive long distances between birding sites we decided to limit ourselves to walking on our big day.

We started our day at 5 am, working south along the Rivanna Trail from Meadow Creek towards Riverview Park. We’d hoped to pick up an owl or two pre-dawn, but we were surprised by how quickly the songbirds started singing, obscuring any owl that might’ve called. The first birds we heard were eastern bluebirds calling from the Pen Park golf course across Meadow Creek from us. The bluebirds were soon followed by a cacophony of northern cardinals, American robins, and common grackles which kept us company all the way until dawn.

As the sun rose, we entered the paved section of Rivanna Trail that leads from River Road (north of the Route 250 bridge) to Riverview Park. The birding was relatively slow, but we did pick up common breeding woodland songbirds like eastern wood-pewee, great-crested flycatcher, white-eyed vireo, and a single common yellowthroat along the river. An orchard oriole sang from the tall trees by the Riverview parking lot.

Once we reached the Riverview Parking lot, we continued into the neighborhood beyond, walking towards the Riverview Cemetery. The cemetery is located on a hilltop, and from it one can see not only the Rivanna River floodplain below but also the mountain ridges beyond. We spent about half an hour in the cemetery, watching for interesting flyovers. Cedar waxwings were abundant flying back and forth between the large junipers and holly trees, and we also saw a Cooper’s hawk and a belted kingfisher. Unfortunately, probably the best bird present was a duck which we failed to identify as it disappeared behind the trees.

As we walked back north along the Riverview Park trail, we encountered a small group of active chickadees, vireos, and gnatcatchers. Hoping the small mixed flock might contain other species, my brother began making “pishing” noises to attract the birds. Suddenly, a chunky, olive yellow bird flitted across the path. Hoping it might’ve been a mourning warbler, we redoubled our efforts. Sure enough, a few seconds later, the mourning warbler popped back up on top of a tangle of grape vines. It had a complete pale gray hood, pink legs, a yellow underside, and the very faintest traces of eye arcs.

A little further along the trail, we were startled into stopping by another duck zooming overhead. Like the one at the cemetery we barely had time to get on it before it disappeared behind the trees, but this one’s large size, long neck, light color, and contrastingly dark head were enough to identify it as a female common merganser. Common mergansers have started breeding on the Rivanna River in Charlottesville in recent years, but they’re by no means common, so it was a treat to see one for our big day. An American redstart, a silent Trail’s flycatcher (willow/alder) and a second (!) mourning warbler rounded out our time at Riverview Park.

As we crossed Meadow Creek into Pen Park, we simultaneously heard the sharp chip of a blue grosbeak and the melodious trill of a pine warbler coming from the golf course. We were unable to locate the blue grosbeak, but we did eventually find the pine warbler calling from a large pine in the golf course. We furtively edged our way around the golf course and then continued north along the trail next to the river. One of our main targets there was prothonotary warbler, a bird that breeds along the James River but is very scarce in the summer along the Rivanna. However, we’d seen one along that stretch of trail at Pen about a week before, so we hoped it might still be there. One individual also apparently summered there in 2019. Sure enough, as we rounded a bend in the river, we heard the loud “sweet sweet sweet sweet” song of a prothonotary warbler coming from the opposite shore. We scrambled down a steep bank onto a small sandy beach to search for it. Eventually we located it in a tree across the river from us, but I couldn’t manage more than abysmal photos. We did pick up yellow-throated warbler and a pair of mallards though. As we continued along the trail we flushed a gray-cheeked thrush — an uncommon migrant and a city lifer for me.

We emerged from the trails at Pen Park along Pen Park Lane in the Lochlyn Hills neighborhood and decided to walk to Lochlyn Hills Park, which is another spot with a good view of the sky, to eat lunch. In addition to many more cedar waxwings, we saw both red-shouldered and broad-winged hawks as we were eating.

Unfortunately, after lunch the birding slowed down significantly. We walked back along Meadow Creek towards Melbourne Road, and then up the trail along the John W. Warner Parkway towards Greenbrier Park. At Greenbrier we added wood thrush and pileated woodpecker to our day list, but nothing else. We finished the day sky watching at McIntire Park without adding anything new.

We ended up seeing 66 species of birds (plus the Trail’s flycatcher) and walking a little over 15 miles. Doubtless we could’ve seen many more species had our effort been better timed with spring migration, but it was fun to explore the city during a slightly less frequently birded time of year. We were rewarded with several interesting breeding species, and a handful of uncommon migrants. It’s amazing to me what natural wonders live right outside my door, even though I’m now living in Charlottesville City.